Boeing is no stranger to 3D printing. Just a few months ago, the aviation giant even filed a patent for a levitating 3D printing process that is supposedly perfect for airplane parts. But Boeing’s engineers are clearly thinking about more than just 3D printed metal engine components or plastic cabin interiors. In a new patent application, Boeing proposes a remarkable 3D printing solution that could make planes a lot safer: 3D printed artificial ice shapes that can be used to simulate icy flying conditions. Not only would they make aircraft certification processes more detailed and stricter, these 3D printed ice shapes are also far more cost-effective than existing models.

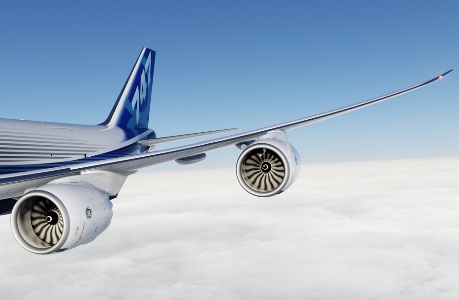

If you’ve ever been out for a walk on a winter morning, you’ll have seen the grass covered by gorgeous ice crystals. These are formed when supercooled water droplets touch a solid surface. A delight to see when you have both feet on the ground, but a real hazard for airplanes everywhere. As a plane’s aerodynamic shape is crucial for a safe flight, a significant build-up of these ice crystals on the wings or the tail of a plane can seriously increase the chance of a disastrous crash.

That’s why the international authorities that provide aircraft certification stipulate that all new aircraft designs need to be tested in ‘known icing conditions’, through a ‘Flight Into Known Icing’ or FIKI. ‘Such certification test flights may require that the aircraft be flown with artificial ice shapes attached to wing and/or tail leading edges,’ Boeing writes in its latest patent application. ‘Dry air flight tests with artificial ice shapes installed allows airplane performance and handling characteristics to be evaluated in stable dry air conditions and with the critical ice shape remaining constant.’

These artificial ice shapes must, of course, mimic the properties and roughness of actual ice. Currently, these shapes are usually built right on the wing using fiberglass and resin materials, and are attached with bolts or other fasteners. The models themselves are based on actual ice buildup, as measured in a supercooled wind tunnel. A brave pilot finally takes the modified airplane into the skies to test exactly how the plane performs when burdened by this unpleasant load.

But this testing process is, Boeing argues, hampered by drawbacks. For starters, it’s costly, very time-consuming and can even damage the aircraft in question. But more importantly, the testing method is quite imprecise and cannot be easily modified for different icy conditions, making it impossible to test a wide range of variables. 3D printing, however, doesn’t suffer from these problems. That is the core message sent by Boeing innovators Cris Bosetti, Fred Krueger, Ian Gunter and Dean Walters, who authored this new patent application (number US2016076968).

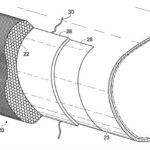

In a nutshell, they are calling for a new certification process involving 3D printed shapes that mimic ice build-up and are significantly more cost-effective. These artificial ice shapes, they write in the detailed patent, can be made from 3D printed plastic, composite materials and even metal. In what they envision will be a very streamlined production process, engineers can rely on a library of various ice-like shapes that have been designed to adhere to airfoil surfaces with double-sized adhesive, rather than bolts. Not only would this create a firmer hold, but it also ensures that the wings are left undamaged after the test flight. What’s more, engineers can easily switch various ice models around very rapidly.

The 3D printed ice shapes (which are thus not actually made from ice) can also be very varied. Engineers can even just assign various properties to a CAD file, such as density, rigidity and texture, and 3D print the final model. The ice shapes can even, they write, be built up around existing blocks to save time and feature built-in identification codes to further streamline the testing process. All this will theoretically give the testing engineers a lot more control over the simulated circumstances, and allow them to test every possible icy condition. In turn, this will allow them to make the certification process far more rigid and detailed, which ultimately makes planes so much safer.